Here is the part where I yield; I concede that this homily on running may not have that inspirational tone that launches a couch to 5k, or makes you dreamily think you could run ultramarathons through the Copper Canyon. I thought that’s where this run was taking me. There were many bends in the trail that proved otherwise.

I turned into 2020 riding high after finishing my first trail half-marathon. Intentions were to ride that crest of good health and fitness into the spring, staving off some embarrassment during student/faculty basketball and hopefully being ready to compete in another year of Time Laps, a 24 hour team relay race that had both decimated and uplifted me the year before.

Of course, no 2020 reflection would matter without the COVID impact, and our school shut down in the middle of March. No more Friday morning pick-up games as a source of fitness, but the potential of an outdoor race still seemed possible. Many inspirational go getters posed that what you did during this period of potential self-improvement would define where you went moving forward.

At that time, when teaching started getting topsy-turvy, running was at least something that could still make sense, something that continued the illusion that things might return to normal soon. I could safely get out of the house and run the local greenway. It became a source of pride for me, that I could use this time effectively and grow stronger. Soon, the greenways began to fill up as people bored with their lives rediscovered local parks, but a ban on people driving to the park gave me a brief reprieve, the illusion of my own private woods to run through. Through the craziness and uncertainty, these woods and trails were my mental escape as well as my physical proving grounds. I was running at least every other day, increasing distance through the middle of April. If Time Laps happened, I would have been in prime form. I had even begun to calculate the feasibility of that fabled 1,000 miles in a year plateau.

And then, one sunny April morning, I was shooting baskets in the driveway when I misjudged the distance between the concrete and the grass and it all came crashing down. I rolled over my left ankle, felt the pop, screamed in anguish. I’m no stranger to rolled ankles, but a quick “walk-it-off” showed this to be a bit more serious. Even if a race would be held, I would be incapable of running it. It wasn’t broken, but it was bad enough that I had to get x-rays, bad enough that I used a cane to get around, bad enough that I spent a lot of time on the couch, sinking into the despondency that often happens when an injury sidelines us.

Here is where I would like to tell you that I learned to slow down and be grateful. But the malaise was too much. I was patient. I did rehab exercises. I did some really slow yoga, which–to be fair–was probably the yin that my go-go-go yang running needed at some point. In those moments lying around on a yoga mat in the yard, I imagined yard projects for the summer (since it became clear that our 10 year anniversary travel plans would be cancelled). Only seven weeks later at end of May, the end of the strangest school year to date, did I eke out a few two mile runs just to test the ankle.

Here is the part where I admit a certain guilt and privilege in writing this. By now, it’s summer vacation for me, and though I lose some income in the summer, there are people in this country who are far worse off than I am, far more desperate for justice than I am. Having to loll around for six weeks and not run while still having a job, while still having the ability to go to the doctor and get that x-ray, while still not in financial stress–all of this seems too inconsequential to be so crushing. So while I despaired at not running, I also reproved myself for having this anxiety amidst so much real crisis.

So, running became a dithering interest. I didn’t stress myself to do it. I would run when I realized it had been a few days since I had done so, but not yet with the fervor with early days of the shutdown had brought. Running (and for that matter, writing) seemed at times like a trivial enterprise. Worrying about not being able to run seemed elitist and indifferent to the pain of others.

Perhaps nowhere was this more true that the questions regarding our return to school–an uncertainty about how classes would work, how I would be teaching, how my life would be configured. Hours and hours and hours in front of a computer, reading conflicting press releases. And then once school started, more long hours in front of the computer, trying to do enough, to be enough to shoulder the burden. The space and time to run often became an afterthought, squeezed into a tight space, just enough to come up for air.

Here is the part where I attempt to re-balance the universe, create a space against the caffeinated, task-driven, omni-alert consciousness that began pervading my waking hours. Running is a space that briefly burns the karma, allows one to think without having to act, to allow the fractured pieces of task and inspiration to coalesce, to step away from a problem and turn it over in the mind as the miles melt away. At least for the first quarter of the next strange school year, running was the mental crutch, often the one thing that got me through days of seeming futility

As the year began to work its way into the colder months, I began to see running friends posting their 1,000 mile accomplishment. What can sometimes seem an inspiration can at other times seem a condemnation. The injury had all but assured that I would never sniff that hallowed ground in 2020, but what was worse, positioned as the role of mental health treatment, running had started to become routine, pedantic event. The beautiful greenway that had been my salvation, my liberation, in the spring, settled into one more mundane routine, one more task to accomplish. My running seemed pointless, perfunctory, and at times, not worth the effort. I needed a jump start.

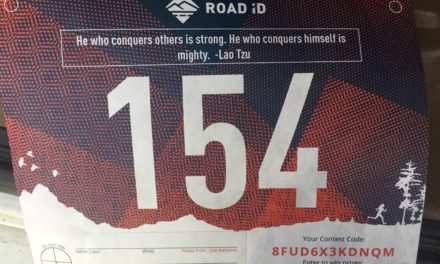

Because the algorithms of the internet know me better than I know myself, Howl at the Moon, a night trail race at the USNWC, showed up on my social media feeds. The jump start I needed. One of my favorite races, twisting and turning through the trails at night under the magical light of the full moon. I hadn’t had a clear race goal since my injury, and this felt like the motivation I needed.

Here is the part where I hold a mirror to myself. Running is a brutally honest friend. Pushed against the limit of your pace and distance, discomfort can tell you exactly where you stand. I learned this in my own humiliation on October morning. I got back on my first mountain bike trail in months, a four-mile loop that was my short run last year at this time. It. Kicked. My. Ass. I was gassed two miles in and found myself walking more hills than I care to admit. A summer of injury and an autumn of piddly short runs had left me a shell of last year’s form. I told myself, that at least I had come and done this, at least I knew where I stood. I knew where I needed to grow, rerouting runs up and down the hills of my neighborhood to gain endurance. Adding a little more strength training to work muscles in different ways.

Here’s the part of the story that should be the triumphant running of the night race, but you’ve likely guessed that was not the case. The race for so many reasons, was an unsatisfying experience. COVID restrictions led to a staggered start, but the starting line was double serving as a pathway to the Illuminated Forest, a popular nighttime destination that put strollers and smokers up and down the initial parts of the trail. Couple that with my inattention to battery strength as I entered the trail, and it was clear that I would be running in muted light.

Less than half a mile in, it happened. Half-distracted by illuminated mushrooms off the trail, I failed to clear a root and turned over the left ankle. I heard it pop again. Race over, I thought, here to anguish alone in the dark as runners moved past me.

Perhaps at the end of this, I can count actually finishing the race as a win. After a good minute of stretching, I figured I could run it off, albeit slowly. The pain stayed with me as a gingerly worked down the trail to the open-field straightaway, but the endorphins and adrenaline began to mute its screams. I got to the long, steady hill and climbed it without stop, the full moon framed by the trees in the night sky; in another year, in another story, this is the moment of pure running ecstasy. I plodded step by step, barely able to drink it in. My light now almost gone, I followed the path of others until I came to dodge more pedestrians to the finish line. There, everyone quickly realized that the course “felt short”, and an brief triumph of finishing the trail 5k was muted by the fact that it clocked in at a measly 2.1 miles. My time was too embarrassing to remember, and I spent the next couple of hours hobbling around with a beer in hand to see if there would be any t-shirts left over.

There was some satisfaction in not quitting, but the race itself felt like an afterthought. Again, I would be nursing a bum left ankle, just as I had started to find some internal motivation that was making running exciting again.

Soon the calendar will flip. Here’s the part where I should say something pithy to wrap this all up, to give 2020 some meaning or some take away that makes it okay, or look hopefully into the future. I waited out my ankle for another week and a half and found it working okay, though as another year passes I know my body never truly heals as much as I would like it to. Aspirations of future races have started to form in the conscious future, and running is starting to be fun and beautifully spiritual again. But as for 2020, it would be trite to say that running got me through one of the strangest years in my lifetime. It’s more accurate to say that running was there all along, and for that I am grateful. I imagine that a story of malaise and stops and starts, of futility and frustration, is one that many of us, runners or not, can relate to. People often refer to distance runners as “endurance athletes”, and it’s strange to think that life itself is becoming the ultimate endurance event of all, in which running seems like an exit strategy for coping. While not being able to run brought this into focus, being able to run also showed than running was no magic solution to make it all better either.

On the Saturday after Christmas, I take the afternoon, for a nice long run in the intermittent cool sunshine and cold shadows. The run is for no reason but for the space and time I have for it. It is enough. Running can be its own mental trap when we feel we have to go further, faster, and for more glory. At a basic sense, it is a simple act of putting one foot in front of the other, over and over and over. I’m in no hurry. I don’t need a mental health solution. I won’t post numbers or tell anyone where it leaves me for the year. It is long and slow and wonderful, the most beautiful hour and a half I have had in months, the cadence of crushing gravel and pushing breath. Step after step after step.

Recent Comments