All this is true, more or less.

Teachers are consigned to a certain type of purgatory. Not hell, mind you. It is not punishment. Just a stage where you work through things. While the each generation of people moves on into the adult world, only reminiscing of their school days in hazy shadows or half-remembered dreams, teachers— being the conduit of ideas for the next generation—relive their own educational experiences every time they discover some slight comparison in their own classroom. Over and over and over. Call it the eternal recurrence of education, I suppose.

The value to this phenomenon—if there is one—is that we have the opportunity to re-evaluate what we are taught, as opposed to letting it settle deep into our the recesses of our mind, background noise for our beliefs, forming our conscious opinions and reactions unconsciously. Unexamined, the lessons of the past take root and help define us—for good or for ill. Reviewing what we are taught by the experiencing of re-teaching it, or questioning its validity, places us squarely in the stream of time, hopefully a check against becoming stagnant.

But the moment it happens is like an eerie déjà vu’. You’re bopping along, teaching your ass off one day and you know the lesson you are teaching, the material you are covering. Except once you were the student. Now you are the teacher. The paradoxes this switch creates can be unnerving.

I found myself in one of these pretzels the other day. It’s Quarter 2 in philosophy class, so it’s time to study religion. For a solid month and a half, it is an ongoing discussion of God’s existence, the ongoing battle of faith and reason, arguments and justifications of faith, and the variety of religious experiences—common and absurd—around the world. I often privately joke that those joke-ass politicians and preachers who lament the lack of God in schools should stop by my room during this time, as there is probably more talk of God in that room than almost anywhere in public schools.

But Thursday might have been the icing on the unleavened bread. It started before the first bell of school. One of my English students sheepishly brought me a Ouija board. His girlfriend was presenting a project on Spiritualism: she wanted to use it as a prop, but she didn’t want to endure the spiritual shade she would likely receive for toting it around school for two periods. Could he just drop it off? Sure. It seems that her suspicions were right, as I got a bit of a sacred stink-eye from students and staff alike just for having it next to me. I put it atop a bookcase in my room and thought little of it until the class arrived a few hours later.

Three hours later came philosophy. A project on Jediism. Spiritualism project was next, but the connection to the spirit world was broken as the lunch bell rang. A few of my students asked if they could take the Ouija board to the library and play. I flinched.

“Just don’t tell anyone I sent you. The last thing I need is the reputation as the Public School philosophy teacher who sent his kids to contact the devil in the library.”

My fear comes from a fairly well-founded place. As a young child I remember frequently going to church youth camps and meetings. The exact details are fairly sketchy, but I remember spending a fair amount of time…Sunday school, Summer Camp, Saturday seminars…in organized religious-based youth meetings. Lots of teaching from a “Biblical World View” goes on in these places. And perhaps what I remember most about these meetings are the warnings about the trappings of the secular world, the kind of things we should be wary of to be “In the World and not of it.” They never approached the level of “Hell House” for shtick, but the message was clear: the secular world is full of spiritual pitfalls. It’s bits and pieces of memory, really, but public school was often characterized as an obstacle course of temptation to lead the soul astray, so much that parents often experienced guilt for sending their students to be taught in that den of thieves–the public school classroom. I remember hearing that Led Zeppelin snuck Satanic messages into “Stairway to Heaven”–the speaker’s prom song. I remember hearing that science and history might try to sway you against the way the Earth was really created. And I definitely remember picking up somewhere that messing around with Occult material like Dungeons and Dragons and Ouija boards was basically inviting the devil into your soul, ensuring you a one-way ticket to the dark side. And not the cool one with the Death Star. The one with eternal fire where you have to perpetually watch crappy after-school specials with an incompetent teacher, where you can have only one salad dressing for all eternity, where you are consigned to infinite Cleveland Browns fandom.

And if I’m to believe what God’s Not Dead claims, there’s nothing more godless than a philosophy teacher who challenges religious arguments as part of his curriculum. I could hear the angry, uninformed script letters from Ralph Reed and the AFA basically writing themselves. So after lunch, when the students returned and actually used the board in their project—admittedly with a condescending and sarcastic attitude to the Hasbro product’s mystical powers—I can’t say that it didn’t unnerve me a bit.

But the project concluded. On to the main lesson. One I had spent quite some time mulling over. We were at an intersection in class where the infinity of ideas came against the finite nature of class time. Buber may have argued that this is how we understand God, but for me it was where I tried to synthesize the ideas of nihilism and religious existentialism in the course of about 50 minutes.

“Vanity of vanities. All is vanity.” If there is a more succinct nihilistic sentiment, I can’t recall it. Solomon, who the Judeo-Christian tradition claims as “the wisest man alive, searching for meaning in the meaningless world, finds that all of human endeavor was pointless, that nature would follow its random course with or without him, and he would eventually die, his life the proverbial dust in the wind, dude. My students felt the weight of these notions, but none of my students could place the source.

“Nobody knows where this comes from? None of you?

Crickets. Silence. The ineffable void.

“Bunch of damn heathens,” I mockingly scorned them. “Book of Ecclesiastes. Most beautiful book in the Bible.” They were duly amazed that the Holy Book of two major world religions grappled with the nihilistic sentiment, when nihilism seems to strike at the very heart of faith. Although I had been raised religiously, I didn’t find Ecclesiastes until I was in college, already beginning the wane of my church attendance. It spoke to a similar creeping dread in me, spoke to me like few parts of the Bible ever have; I both revere its sentiments and question its conclusions to this day. The creeping dread of nihilism, I often tell my students, is a problem we all face from time to time.

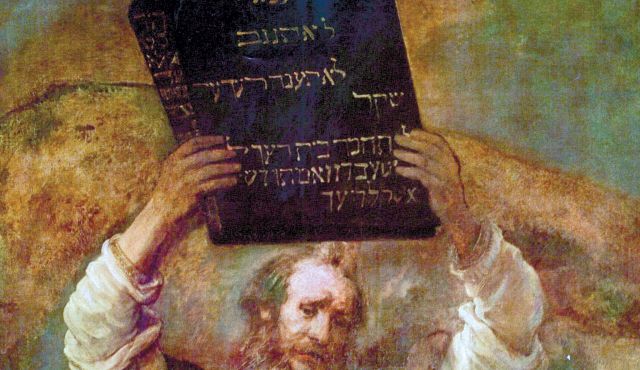

We discussed why people feel this way, and how religion addresses this fear of being nothingness. I related Kierkegaard’s epiphany—that all true connections with the divine are marked by absurdism and ineffable paradox and should be approached with laughter—by narrating the story of Abraham and then moved to the story of Moses and the Ten Commandments—spending 40 days in the mountains, the revolt of the Israelites, the smashing of the tablets and the bitter water-as as an example of the rocky mystical beginnings that blossomed into established religions. They were rapt, like six-year-olds in Sunday School. Many admitted they didn’t know any stories from the Bible. They were hooked on these tales I had taken for granted, the same stories I had heard over and over in my primary education.

Here’s where the paradox begins to strike me. If I were to go back to lessons of those youth conference days as a public school teacher who allowed a Ouija board and a faux-séance as part of a project, I would be a pariah, the very archetype of all that is most wrong in Public Schools. I would be the epitome of the darkness they fight. If, on the other hand, I were the Public School teacher who made the kids—many of whom had never read the Bible—read KJV OT followed by laying down some primary Sunday School stories, I might be something of a hero to the flock, the lone light shining in the darkness. Pat Robertson might even say some nice words about me right after Harry Potter went off, right before condemning “the gays.”

Here’s where the paradox begins to strike me. If I were to go back to lessons of those youth conference days as a public school teacher who allowed a Ouija board and a faux-séance as part of a project, I would be a pariah, the very archetype of all that is most wrong in Public Schools. I would be the epitome of the darkness they fight. If, on the other hand, I were the Public School teacher who made the kids—many of whom had never read the Bible—read KJV OT followed by laying down some primary Sunday School stories, I might be something of a hero to the flock, the lone light shining in the darkness. Pat Robertson might even say some nice words about me right after Harry Potter went off, right before condemning “the gays.”

Of course, neither of these is true. Philosophy and education in my classroom are all about finding the position a student is in and giving them a nudge, ever so slightly, so that they can grow. I certainly have my beliefs about the world, and I could never extract those beliefs from who I am even if I wanted to. But in the classroom, it is not the ego nor the agenda of the teacher that should matter. My job is to shine some light on the path they tread. Their job is to figure out themselves and their path in the world. I do my work and step back. We are there to reveal, elucidate, inspire. We are not there to indoctrinate.

Thursday dwindled to an end. But the paradox I discovered in myself and my teaching? I can barely describe or speak of, which is probably why I tried to take a few thousand words to do so. How bizarre that the kid from those youth conferences would grow into the teacher who both met and defied those lessons within one class period. How absurd. I found myself laughing as I locked the door on my sacred space for the day.

Recent Comments