Q: What’s the difference between a Yankee and a Damn Yankee

A: A Yankee comes from the North. A Damn Yankee doesn’t go back.

As a carpet bagging ten-year old moved from the suburbs of Boston to the rural red clay of North Carolina, I was told this “joke” more than once. Surprisingly, smart-ass me reminding the kids on my bus that The South lost the Civil War didn’t win me any new friends. It did establish early for me that some people in The South don’t really take kindly to people from the outside telling them how to do things. And the further along I went in school, it always seemed to me that the more people wore “Southern” as an identity, the more this tendency expressed itself, reminding me that even though I’ve lived three-quarters of my life in this geographic region of the United States, that I would never truly be from here.

So, I’m not going to lie: I experienced a bit of schaudenfreude at the expense of my adopted home when I slipped down a Twitter hole for the second time in a 24 hour period. The first was watching the Twitter-verse roasting erstwhile Rage Against the Machine fans for criticizing the band for injecting politics into their music, as if this hadn’t been the MO of the band all along. Really? How could anyone listen to songs like “Know Your Enemy” and “Killing in the Name of” (literally the repetition of “some of those who run forces/are the same who burn crosses” is the first verse) and not know where the band would stand in a moment like this?

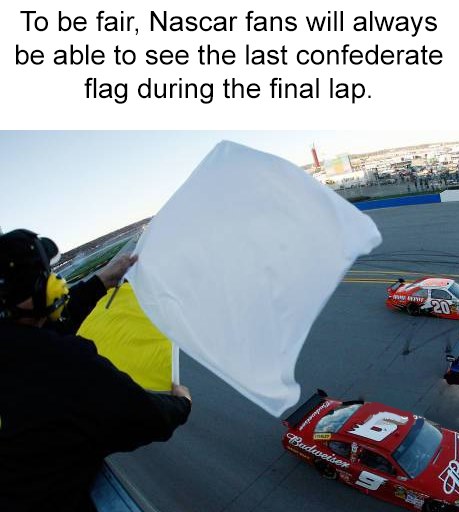

But I digress. The second slide down the Twitter-hole was watching NASCAR’s official social media platforms explode as they announced officially that they would no longer allow the confederate battle flag at their tracks. Some people came to renounce their fandom. Some people came to mock those people. Some people came to praise NASCAR, and even say they were more likely to go to races. Some came to make historical arguments. Some, like myself, came to watch the shitshow go down.

I was not disappointed.

Perhaps this is not too surprising, but banning the Stars and Bars became something of a line in the sand for some people. The nation has been in various states of civil unrest since the murder of George Floyd. But for some people, losing their flag in the sport that was built and grown in this area of the country seems like they were losing a vital part of their culture, their identity. The South may claim supremacy in College Football, but NASCAR was literally built in The South from moonshiners juicing up their cars to outrun the fuzz. Its expansion across the country has darkened the tracks at smaller locales like Wilkesboro and Rockingham, but for many southerners, NASCAR is homegrown and as southern as sweet tea on your front porch and mater sandwiches you just picked from out back. Having NASCAR reject this symbol of the South was quite a mighty blow.

On some level, it shouldn’t be that surprising. It would be easy to say that taking the flag down is something of knee-jerk reaction to the aftermath of Floyd’s murder. And while it is true that high-profile hate crimes (like the Charleston Mother Emmanuel shooting) or murder of African Americans at the hands of the police have accelerated calls to remove symbols of the confederacy (statues included) this effort has been going on for sometime now, and is only gaining momentum (as the fall of Silent Sam at my beloved alma mater recently proved). What is different is that it is completely untenable for a major corporate sports franchise to continue to grow in Modern America (especially at this point where it is one of the only games in town) and allow racist iconography to proliferate within its stadiums. If in three years, the NFL has basically had to backtrack on its kneeling policy (for which they blackballed a star quarterback), it is clear that the winds have changed for corporate America. And NASCAR knows this.

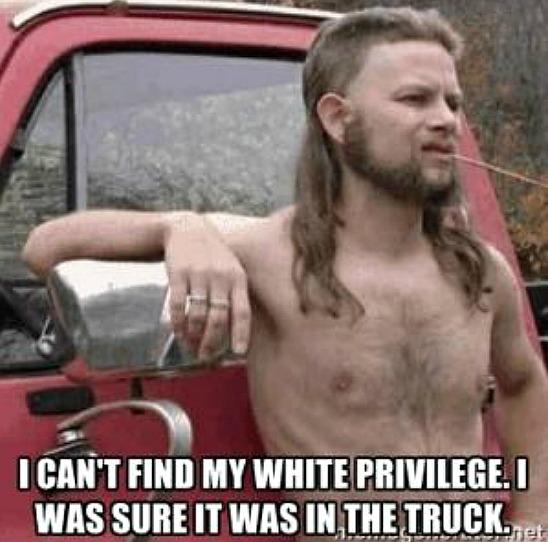

The challenge for Southern whites, it would seem, is that they feel that because of all this going on in the world, they are the ones who are losing something. And it leads to a phrase I’ve seen online quite a bit, a phrase I’ve argued with people over: White Guilt. Floyd’s murder and the outpouring of protests against the police across the country have led to a massive volume of individual stories of mistreatment at the hand of the police. For a lot of white people, this is uncomfortable. It creates discontent in a white world view that thought that after MLK marched on Washington (or even Obama was elected President) that the Klan magically disappeared and all of our problems were solved. As one person who I recently conversed with said: “I work hard. I don’t hurt anyone. Why should I have to feel guilty?”

My answer is you don’t. Guilt somehow suggests you’ve done something that you now need to repent for. And as many people feel that they were also born poor and worked hard to earn what little they have, the suggestion that they have something to atone for really chaps their hide.

So, let’s admit this is uncomfortable but hold off on calling this guilt for now. Let’s just talk about the discomfort and where it arises. And for this point, the confederate flag actually is a good starting point. Let’s say your whole life, you’ve had the confederate flag around you. You’ve lived your entire life in a fairly honest and upstanding way, and you see this flag as a part of your heritage. You reject that it means hate. You know about the history of the flag and where it came from. But then someone presents you with the facts that the Confederacy that flew that flag openly discussed the necessity of keeping a slave system in place. Or you discover that white nationalists worldwide (not just the homegrown Klan) use the Confederate flag when the march against people of color. Or you simply discover that some of your neighbors don’t see the flag with the same reverence and honor that you do. This can create a moment of cognitive dissonance, where our subjective reality comes into conflict with the world around us, and we must navigate that discomfort. It happens all the time, but cognitive dissonance can be particularly difficult when it challenges beliefs that form the core of our identity.

Many Southerns and flag holders are put in that moment now by the actions of NASCAR, as one of their institutions rejects one of their core symbols. And it’s really tempting to fall back on that this is not what the flag is intended to mean, or that that’s not what an individual means, and then simply look at the world like it’s going cattywampus and the person who knows the history of the flag is right but just misunderstood. It’s the rest of the world who gets it wrong.

But let’s break down the flag as symbol. Any public symbol (and the flag is certainly one) is a speech act. There is the intent of the speaker. There is the context of the speech (symbol or words) that gives historical meaning. Then there is the interpreted meaning of the audience who perceives the message. Sometimes, these things all align, like when you see a red light and everyone knows it means “Stop” (except for Charlotte drivers). But sometimes the three legs of the stool don’t align. Even in words, there is often misunderstanding that we must backtrack, re-explain, and negotiate, to make ourselves understood. For symbols, this can be even more precarious. Falling back on an argument that “this is what the flag means” or “this is what it means to me” ignores the third leg of the stool; the meaning perceived by the audience.

People are often quick to dismiss this, but do so at their peril, because doing so ignores the fact that language is dynamic and changes over time. Consider that “leg” was considered a vulgar word for its suggestion of unclothed skin in Victorian England. That seems patently absurd to us now, but it was the overly-prudish social more of the time. People might argue that the “leg” example doesn’t have the same cultural weight as the Confederate Flag. They would be right. So, let us consider another example.

The Swastika is an ancient symbol that has been in use for thousands of years in Asian countries. Historically, it has had positive, nurturing meanings such as good fortune and health. It was used in advertising for centuries. Then some pasty dude with tiny mustache came along, co-opted for the flag of Germany under the Third Reich, and changed the connotation of Swastikas (and Chaplin-style mustaches) forever. And even to this day, that symbol still gets used by White Supremacists groups.

I think you can see where I’m going here. Let’s say that I’m Asian, and I want to display my heritage by putting Swastikas outside my house for good luck. In America, I actually have the right to do that, because it’s my private property. And I can claim that is why I’m doing it. And I can explain the historical background. But the truth is, every person of Jewish descent, and indeed any person who understands history, is likely to feel revulsion at that symbol. I might be free to put that up on my property, but that doesn’t mean I’m immune to other people’s opinions. And when we shift to the realm of public spaces, there is no guarantee that this symbol has to exist, especially if the owner of that space (be it corporate entity or government) has the mission to make people feel comfortable, safe, and at ease in that space.

Let’s be clear. The South is not the only region of the country guilty of a racist past or present. When African Americans migrated in drives to northern cities to seek work in the early part of the 20th century, they were just as likely to experience systems of oppression as they did down South. I had somebody suggest the other day that because I was originally from the Boston area, that moving South must have been a shock for that reason. Admittedly, it was (for lots of reasons) but as I grew up, I learned that Boston has its own disgusting past with racism, just like many places throughout the country. It is a legacy that we are only starting to awake to in this country. Unfortunately for the South, it’s the place where the racism has been the most entrenched; it’s the place where are the most public symbols erected to a nostalgia for that time period where slavery was defended as virtuous and ordained by God. As Dave Chappelle once famously quipped, it’s right out there in the open, stewed to perfection. So, it’s probably in the South where the most painful growth has to occur.

Plato once argued that the movement from the world of shadows to the world of truth can be a painful, discomforting, and disorienting process, and that many would rather return to the darkness rather than continuing on to the truth. In this case, let’s not use ignorance in its usually derogatory connotation. That gets people defensive. Here, it simply means not having knowledge. The phrase “ignorance is bliss” has its grounding in an allegory like Socrates presents. Ignorance is easy and comforting, but ultimately, it is a shadowy version of reality. Learning the truth can be painful, but necessary to growth and certainly necessary for a movement towards a more just society. After all, if we already thing society is perfect, what need to we have to make changes to it?

James Baldwin made a similar argument in regards to how we view race in his famous speech “A Talk to Teachers,” Speaking to educators, Baldwin makes that simple yet revolutionary statement that Africans were shipped to the Americas to be forced labor to create wealth. And in order to justify this unjust system, a system of dishonest lies had to be used to justify the arrangement, lies that he argues persist until this day. Baldwin argued that in regards to American history, the painful progression from ignorance to knowledge was being able to take away these dishonest beliefs we have about our history, not to hate ourselves or our country, or to feel guilt, but to commit the revolutionary act of telling and knowing the truth. This was the very painful progression that had to take place, not only because it would liberate African Americans from the stereotypes intentionally heaped upon then to justify their degradation as they were brought to this country, but also because it would liberate White Americans from their ignorance about the world around them.

White backlash in the climate of these ongoing protests can be attributed to cognitive dissonance, believing the world is fair and the protesters are the ones who need to get with the program. As always, it’s most visible through pre-packaged memes that show up on my social media feed. One meme claimed that we needed to remember that it was black people who sold black people into slavery (as if this absolved white people of culpability). The second one claimed that there was no way we could be a racist country when we had all-black colleges, all-black churches, all-black bars, and a black history month. The third is that if you have nothing to fear from the cops if you’re doing nothing wrong.

Let’s go from easiest to hardest. The very nature of these protests call out the names of people who were killed by the police for doing absolutely nothing wrong. Tamir Rice. Breonna Taylor. Philando Castile. These names are just the three most accessible on my frontal lobe of a list that goes on and on. Claiming this means you’re either not paying attention or you’re denying the basic reality in front of you.

The second one is also easy to debunk if you have a basic understanding of history in this country. If you’re ignoring the fact that these institutions were a) born of the fact that African Americans were usually excluded from white institutions, and therefore had to fight to have a place of their own and that b) none of these institutions are legally exclusive (i.e. white people can go to HBCU’s and go to a black church whenever they want. The same freedom of movement has not always been true of white spaces for African Americans), you are ignorant of the history of your country, and that ignorance skews your perception of the reality before you now. You believe that an HBCU or an all-black church is a privilege, not an adaptation for African Americans denied an equal footing to learn or worship in this country. You’re using a flawed understanding of history to look at the fact that people are legitimately fighting for justice and interpret that fight as “unnecessary,” especially if it feels like you have to lose something.

The first one was a bit more problematic, but it gets back to the point I was trying to get at about White Guilt. Nobody chooses when they were born, where they were born, or under what conditions. White people don’t have to feel guilt because they were born into a country that used the enslavement of Africans to propel itself to economic prosperity. However, the fact that people are posting this fact supports the strange notion that just being truthful about history is still a revolutionary act.

If white people are feeling discomfort right now, it might be that you’re being made aware of things that you have never considered before. Maybe you’ve never seen the world through the experience of another’s eyes, someone whose experience in the world is profoundly different because of the color of their skin. Maybe you’re waking up to the fact that this country isn’t as just or fair as you always thought it was, as it always claimed it was. Some people have intuitively known this from a young age. You may now just be learning this for the first time.

That can be painful and discomforting. That’s not guilt. That’s the growing of empathy, knowing the struggle of others. This type of knowledge leads to empathy, but that can sometimes be a painful path. Don’t flee from that feeling. Embrace it. Some pain and discomfort is what we need to grow. And as a country, it will be necessary for us to go through pain and suffering to atone and learn from the sins of our past. We can only do this with our eyes open. It doesn’t mean you have to feel guilty for something you haven’t done; it means you need to be aware so that you don’t unconsciously allow it to continue to take place under your own ignorance.

Calling this feeling “white guilt” is often a convenient step to inaction. It’s easy to say, “I shouldn’t feel guilty; I did nothing wrong. I was born poor and worked hard. I didn’t commit the historical acts of racism that lay the groundwork for the system we have today.” And though all those facts are true, calling that feeling guilt is a convenient way to say “I shouldn’t feel guilty, so I shouldn’t feel anything.” Rejecting the discomfort that can lead to growth by calling it “guilt” and then saying “I don’t have to feel guilty,” can be a convenient way around the cognitive dissonance we feel when racism is so blatantly obvious. Then when the fervor and the protests die down, we can go back to pretending it isn’t there.

The real seed of white guilt is you should know better but you choose not to. Like you’ve been listening to Rage Against the Machine all these years, rocking out to the music, ignoring the words that are in front of you the whole time. Ignoring the fact that though our national anthem claims we are the land of the free, this country has been a history of fighting to achieve that freedom. Ignoring the dialogue that comes inherent in a controversial speech act. Reverting back to the belief that you’re right and it’s the entire world that’s crazy. And then one day, the shit hits the fan, all the stuff you’ve ignored came bubbling up all around you. You should’ve known better. In that place, maybe you should feel guilty. But remember that in all great religious traditions that the path out of guilt is atonement Guilt can be growth, too. It’s a painful wake-up call, for sure, as being awakened to knowledge can be.

Recent Comments