It has been a summer of movement, by the end of which I will have spent over a full week of days in and out of airports. It’s a lot of motion, Uber rides, subway rides, bus rides, walking with luggage and airport food. You try your best to be calm through this without developing a drinking problem.

Oddly enough, the days in travel carry their own reverberations. After all, one must pack for a journey and then unpack from returning. This isn’t to complain about travel, but rather to acknowledge that in the hustle and bustle of doing so, there are often limited times to sit and have a quiet morning to sit around in pajamas, sipping tea, composing esoteric blog posts that no one will read.

In short, there’s little time for the mud to settle. That’s an old Taoist proverb. Allowing the mud to settle and for the water to become clear. Or as another writer I’ve been perusing on my travels put it, avoiding the compulsory nature of action, to eschew the idea that our daily routines are at some level self-imposed and often undertaken without actually considering their necessity.

Such is our karma, our attachment to action. This word often cringes me when my students throw it out, a shorthand for “what goes around comes around,”–a divine form of retribution. In a narrow sense, true. In a broader sense, it is the entanglement of all of our actions, one action seems to necessitate both subsequent actions and emotional reactions to those actions ad infinitum. And if our action is compulsory in nature, we are often unaware of how our choices create strands of new choices. Like letting the mud settle, stepping out of our karma seems like stepping back from the effects of our choices and actions.

Easier said than done, even in the summertime. During COVID, I sat in the backyard, injured from running, and envisioned building a space for dwelling, which included a raised bed garden. As a result, I’ve actually gotten proficient at growing some plants while others continue to flounder. Lessons for another season, I suppose.

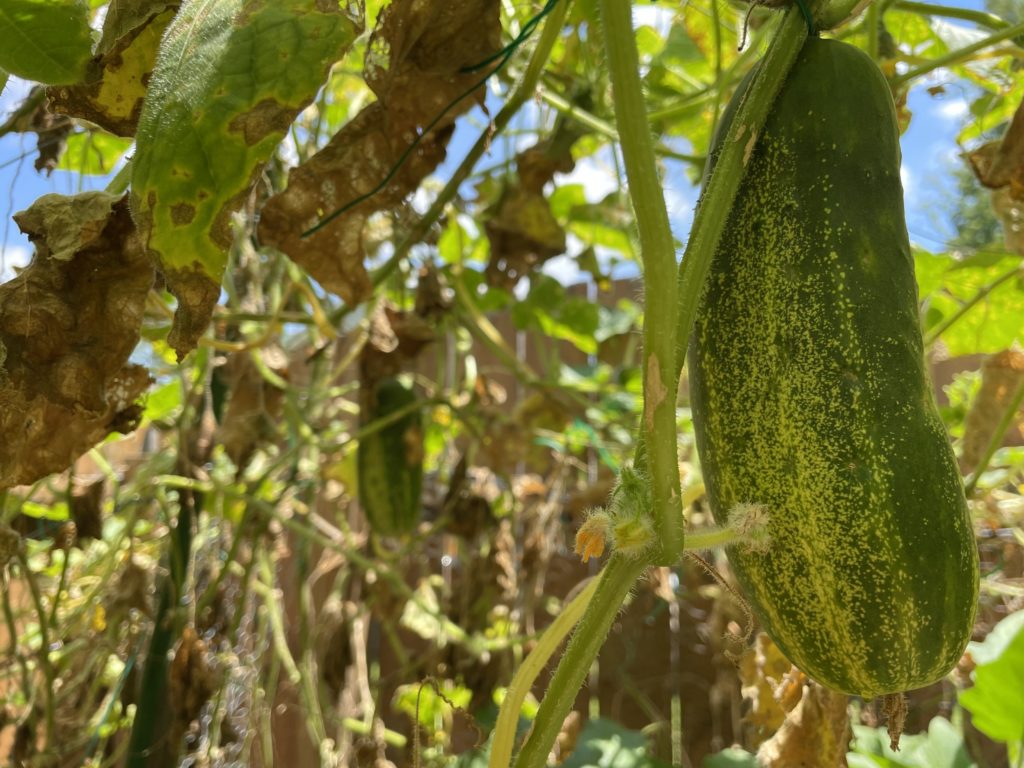

Perhaps the most successful of the plants in my garden is the cucumber. During a moderately successful first year, I watched the vines grow a short cycle and die. In the second attempt, I learned how to trellis their vines to extend their growing season. Cucumber vines, you see, are creepers. They grow as vines, shooting Spidey-web-like tendrils to any nearby surface to aid their growth. If they are planted densely at the outset (as my boxes inevitably are), those tendrils climb on each other. In the search for optimal sunlight, they end up climbing all over each other, creating a knot of vines that ultimately choke each other out before they get a good chance to bear flower and fruit.

In order to optimize their growth, this gardener learned to come in to disentangle the vines and re-trellis them to grow in new directions. Last year, I extended the growing season so well that I ended up making close to 100 jars of pickles and other cuke-related products. Not to brag, but they’re pretty good. Cukes are like the blank canvas of the vegetable world, absorbing whatever flavor you can put on them.

But abundance brings its own challenges, and after heavy rains, the vines grow so quickly that they can be a chore to maintain. In the rain, they grow so fast that a few cuke plants can go from vibrantly growing beautiful yellow flowers that the bees can’t resist to parched, brown vines in a matter of days.

Such is my cucumber karma. I have built the garden. I have planted the plants, and now that action demands that I continue to care for them or allow them to wither and die. So, when I returned from Tampa in mid-June to find a bundle of cucumber vines fighting each other for supremacy, I had to go to work: carefully disentangling vines, building spaces for them to continue to grow, pruning spaces to take out rot. Then I went to Boston. Apparently, it rained while I was gone, and when I returned, I brought in cukes by the armful. More tendrils, more entanglement, more disentangling. More cukes. The result of this sometimes is hours in the kitchen making jars of cucumbers.

And this morning, as the mud settles in some regions in the lake of my consciousness, I still have cucumbers to pick and pickles to create. I could easily sit on the couch, drinking tea and watching Letterkenny. I could easily go to the gym and shoot hoops for a couple of hours. But after the rain, when the mud settles, the cucumbers blossom. This is the action in which I have invested.

This is my karma, the karma I have created through action. The joy of planting cukes in the spring, to invest in them throughout as they slowly grow, and then prune them and lead them as they make it through their short life cycle in my yard. And now? Hours spent in the kitchen making pickles, half of which (at least) I will give away. It is hours of retrograde, unnecessary agricultural work that I have freely created for myself.

![]()

Karma isn’t necessarily removing oneself from the cycle of action, but rather recognizing where one is in that cycle. The sometimes challenging spiritual work of that is continuing to find the joy in the choices we have made once those choices bear fruit (or in this case, cucumbers) We all want to enjoy the fruit and flowers, but we do so by nurturing the roots. And by nurturing these roots, this work, this time in the kitchen is the flower of my action.

Recent Comments