How quickly we slide into old habits, ignoring drafts and ideas to wither. Not today, Satan. Not today. Here’s a draft started around Labor Day. Just now edited and uploaded. Still worth the read, as I need to reclaim my own contemplative space.

Week One in the books. Barely enough time to get into the substance of class. Lots of first week business. Long homerooms. Assemblies. Even in the classroom, there’s a lot of time on classroom procedures.

And since that means I spend a decent proportion of the week talking about technology policies in the classroom, it was a loose thread hanging in the back of my brain just waiting to be pulled as soon as I got into the good grind of a Monday morning paddle.

Yup, it’s Labor Day, brought to you by the reformers who thought that weekends and restrictions on child labor would never come of the kindness of someone’s heart, hence, we needed laws to protect them. Not a bad gamble. As a clear, direct line from that logic, the lake will be chock full of boaters, so my goal is to get out there early and get off quicker than Lawrence of Arabia, before the afternoon sun gets glaring, before the water gets thick with pontoons and speedboats creating wakes every which way.

But now that the school year has started, it’s not just the heat and the other boaters. I often think about what I can do with time when I get home: fix that Canvas problem, reformat the syllabus, get ahead on lesson plans. Even in free and open time on the lake, the choice of doing work instead is always present, threatening to dominate and steal the joy of a morning paddle.

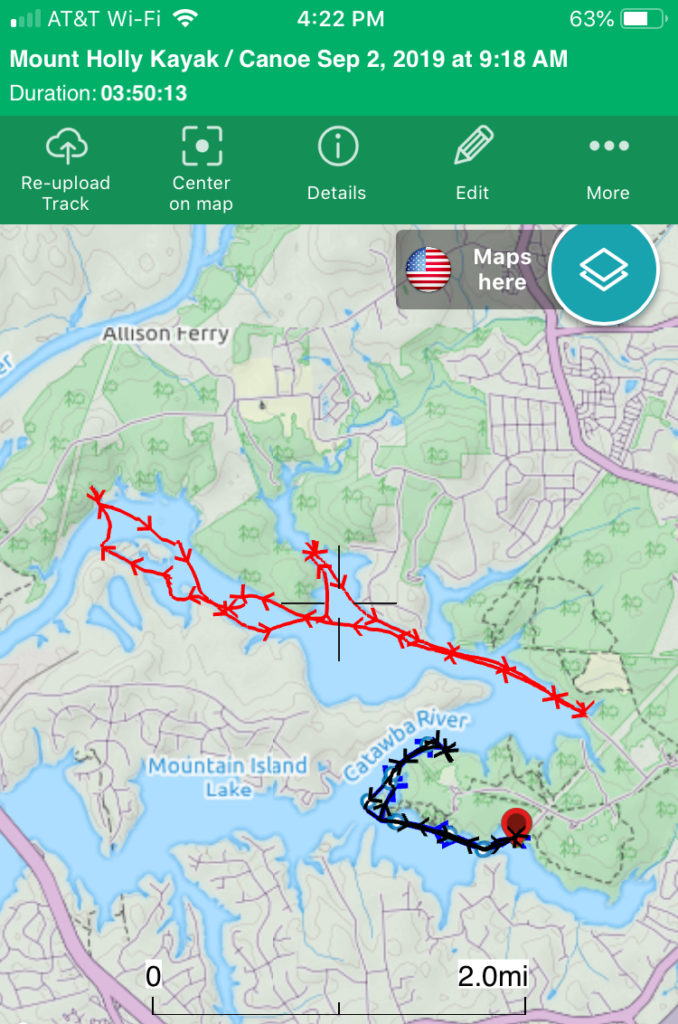

I’m on by 9:30. They must be releasing water from Norman because I’m fighting the current up the north channel. The water is low, and the mid-lake sandbar juts prominently into the air. I keep an eye on the trusty AppleWatch to check the turnaround time, but text messages from my dry bag keep showing up on the display, and since I have it on waterproof, I have to stop to check the time and distance. I know. Technological first world probs.

At any rate, I’ve made a loop into the Catawba River, skirted the volleyball sandbar near the river entrance on the return, and strung up my hammock up in a trusty spot by 11:15. Nice shade. Grab a snack. Doze for a bit and watch clouds degenerate and join with other clouds. Jump in the water for an impromptu baptism and swim, but the floor of the lake is a gooey mud that sucks on the Chacos, creating a murky water pea soup with every touch; so after a bit I’m drying off and in the hammock.

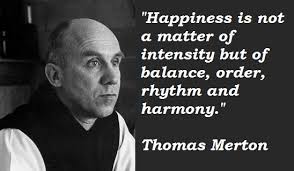

The water has seemed to slow, laying serenely off the rocks in front of me. Now more awake, I pull out the book–I try to always put one in the dry sack. Today’s read is perhaps the physically smallest book I own: On Eastern Meditation, a compilation of ideas from the various works of Thomas Merton, the late Catholic monk who traveled Asia in search of common truths between Western and Eastern religions thought.

Of course Merton, who died on his Asian pilgrimage in 1968, did not opine on the state of modern technology. But the chapter on “contemplation” pulled the thread that had been waiting all day. It’s weird how that happens. I thought I was getting in my boat to give myself a break from school work; I was actively trying to hold work thoughts at bay by paddling further and further, concerning myself only with the issues of physical endurance, health, and happiness.

But the mind wanders where it wanders in the contemplative open space. Merton, in his Asian Journals, writes:

The contemplative life must provide an area, a space of liberty, of silence, in which possibilities are allowed to surface and new choices–beyond routine choices–become manifest. It should create a new experience of time…not a blank to be filled or an untouched space to be conquered and violated, but a space which can enjoy its own potentialities and hopes–and its own presence to itself. One’s own time. But not dominated by one’s own ego and its demands.

I think the phrase “routine choices” first got me down this rabbit hole. What would creating the foundations even be for our students to have even a taste of “the contemplative life” in our pedal-to-the-metal go-go-GO! Classrooms? A colleague of mine recently told me that giving a mid-day class a mandatory 10 minute nap at the beginning of the period was the best decision he’d made for them, but is exposing students to this concept as simple as giving them time back to explore on their own?

I imagine at first that the contemplative life–”a space of liberty and silence” given to my students would look like one of two things. The ambitious ones would take that time to get ahead on other work. The other choice would often be the default choice of whipping out the smart phone and dawdling. Mind you, I’m not using that in an insulting way, and “using technology” is a broad description of myriad things a person could be doing online, from researching how apply for a Rhodes scholarship to playing Fortnite. It’s just that in my own skin, I’ve been currently weighing the value of the 20-30 minutes I spend scrolling through social media, wasting time looking at the same stuff over and over, vs. its other “more productive” and intentional uses. However, it would see that both of these represent the “routine choices” Merton decried. Creating a space for the “contemplative life” is more than just giving students the time to explore themselves.

At some point, they may need some guidance to enter that space. Earlier Merton had described the necessity of teachers in guiding a meditation practice as “a man skilled in catching snakes can catch them but one who is not skilled gets bitten.” Apparently he thinks that one needs some type of skill and guidance to enter this life. Perhaps just giving people more free time is just lazy without structure. After all, even giving kids the directive “take a nap” is a guided free time, not open space.

But that’s at least where this starts. At a school as large as mine, structured with a schedule that plans minutes down to the minute detail, there is certainly limited time for “one’s own time” so that what is leftover is often dominated by “one’s own ego and its demands.” Of course, this is the case for American adults as well, so it is little surprise that we are raising children to follow in our footsteps

So, maybe you’ve got this far in and you’re still not sure how this relates to technology. I started thinking about what motivates our classroom technology policies in the first place. Even as my approach and methods has changed on this issue–from ruling by fiat to reasoning with them that putting away their smartphones is in their best interest–my motivation is the same: technology can often distract from the work that needs to be done in my class.

The arguments for this are myriad and valid, to the point there’s little need to elaborate much. Smart phones distract the learner. They distract others. They can facilitate cheating. Keeping them out of the classroom is effective for the short-term goals of my classroom management and whatever long-term gains the students derive from what they learn while enrolled there. Though they can be tools for education, they are still such a threat to the learning process that some schools are actually become more restrictive, reverting to a “no-tech” policy (here and here) and the very people who develop these near-ubiquitous tools shield them from the potential harms on young minds.

But an article I found and discussed with my philosophy students is shifting my thinking on this a bit. To be fair, I’m not sure where it’s going, but it’s made me think about other motivating factors that should be considered in crafting tech policies. Philosopher Andy Clark proposes that technology is and always has been an extension of the conscious mind. Books, for instance, meant people memorized less but had more knowledge and ideas to draw upon. Hence, any shifts in tech changes the nature of our conscious experience, even going so far as to suggest that we are becoming conceptual cyborgs, our minds inextricably intertwined with the tech that they explore. For instance, my mind on the morning paddle was informed by a watch that kept time and predicted pace, and a phone that both distracted in the chatter of GroupChats and aided navigation and predicted weather patterns. So perhaps keeping it out of the classroom may reduce the distraction in an immediate sense, but the existence of the tech in the student’s life will alter their conscious experience whether we allow it in class or not. As such, we still have to consider what role that plays as they grow into adults.

In school, we often allow ourselves to be reduced to the future skills we can provide students, but this focus on simply giving a student economic skills ignores another, perhaps more important part of that growth: how they will interact with the world beyond their marketable skills? How will they interact with the world? What kind of person will they be?

Going back to the contemplative space, this is, I believe, where these decisions will be made. Unfortunately, when school ignores the space for contemplation and if it focuses only on the skills it provides, it lacks in this important part of a child’s education. We keep asking them “what do you want to be when you grow up?” but don’t consider that regardless of the job(s) they acquire, there are so many other ways in which they must interact with this world socially and emotionally, and increasingly, interpersonal technology is the method by which they will. They would be well-served with discussions of how to best navigate this Promethean fire in a way that an outright ban simply can not encompass. Is this the role of the public school? I’m not sure. But we can be sure that the exponential growth of technological integration will only abate in some sort of apocalyptic world, at which point we’ll have bigger fish to fry. At least in school, we have the youth as a cohesive, captive audience. If not us, who?

As a humanities teacher who reads as voraciously as possible, the contemplative life is something I encourage at some level for my students. Am I trying to make them pan-religious monks like Merton? Nope. Not my job. However, our education, more and more, is geared toward making people effective economic participants and citizens, but says little about who they will be as people, We can’t figure that out for them, and the default settings seem to be work themselves to death and/or lose themselves in a technological malaise. But perhaps thinking about how to provide them with contemplative space that includes an intentional relationship with their technology might be a good first step.

Recent Comments