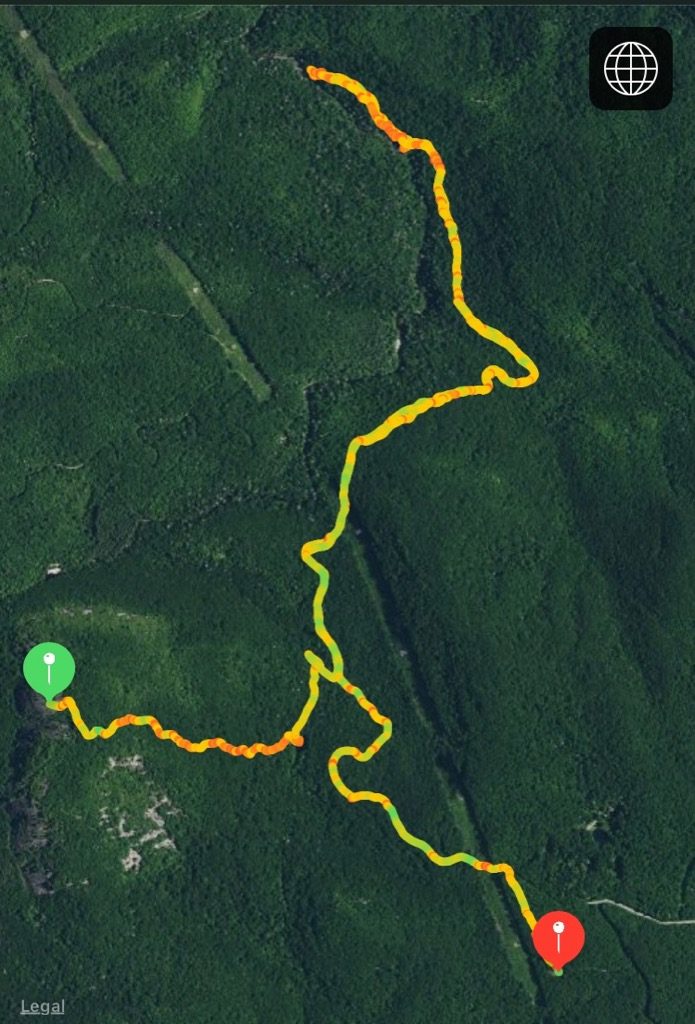

Tranquility Point—Red Butt Falls—East Parking Lot (5.6 miles)

Fog rolls across the valley. A perfect camping morning that makes you want to roll over again in your burrito and hit the natural snooze button. As Red sleeps, I ponder the decision before us.

Choice 1: Do a day hike in the valley exploring one of my favorite features of P-Town—Red Butt Falls. It will get us to our destination—Decatur, TN, a little later in the evening.

Choice 2: Hiking back out to the car. Depending on how quickly we can break camp, we might be there before lunch, which means we can take our time on the road and still get to Decatur by the afternoon, maybe even make some stops along the way.

I choose the former. I’m big on taking advantage of where you are while you’re there, because you never really know when you’re going to come back. While it might mean less time for kayaking, Red is more experienced on the trail than she is the in the boat; when I present Red with the options, she seems on board with more hiking.

So we start the process of the morning. Like all things I find intuitive, having breakfast and breaking camp isn’t natural if you haven’t done it before. I feast on an oatmeal bag I’ve moistened with a chocolate milk I packed in; I boil water for the two packs she’s put in the bag. Predictably, it’s too hot.

When I get in this situation, I just start doing other things to get ready, checking back and having a few bites as the oatmeal cools. So, we decide to start packing up packs. I’ve packed my pack hundreds of times. I know how my pack works, where it all goes, the order to put it together. For Red, this is all new terrain: she’s never put a sleeping bag in a stuff sack, never rolled up an air mattress, never put the pack together. Everything is the first time. If she decides she wants to keep camping with me, the muscle memory will get there, and this will go more smoothly. But for this morning, putting the packs in place is a methodical and didactic process.

When we get everything out of the tent, I tell her to go back up the hill and eat her oatmeal. “You’re going to need the calories for the hike,” I say. But the delay has made the porridge far past “just right”, and while she gamely tries to take a few bites for nutrition and fuel, there is no microwave to rectify the temperature. Cold oatmeal, whether you’re a rookie or a veteran is gross and goopy. If you’ve ever had a calorie crash on the trail, you know you need to force yourself to put it down. She hasn’t, so despite my best exhortations, half the gelatinous glop makes its way into the trash bag.

We’re on the trail again by 9:40. Schoolhouse Falls is quiet when we arrive to top off our water (there’s none on Little Green or at the campsite), but soon two men and three boys come to practice casting followed by a family and their dogs. This will be no quiet beach party. Around 10:40, we hit the trail again. The mom stands agape as she sees Red sling on her big girl backpack and asks us where we are going.

The Devil’s Elbow trail begins as a gravel path, through a power line opening draped with blackberry bushes that we plunder for fresh fruit, then turning into a rolling up and down through shaded rhododendrons and moist conditions. Red begins to create her own taxonomy of the fungus, counting at least ten different kinds that she names by color, shape, and appearance. The sky is overcast, enough to make me worry about rain (as there always seems to be some lurking around the corner in this part of the world), but the weather had said cloudy but no storms, I tell myself. We pass the Ford Trail intersection and then the spur trail that juts left that will take us down to the falls.

Initially, the trail is calm, and we take a quick peek at Elbow Falls on a rock jutting into the Tuckaseegee River. Then we turn back up the hill, and I quickly realize my own hubristic blind spot. I’ve hike this trail twice. I love the falls. But I often remember the glory of the falls and not the challenge of the trail. I’ve only done this hike with a day pack; it is a much different experience with a full backpack on. The trail takes quick turns up and down the hill beneath gnarly trees, and I frequently resort to hands and knees to get my mule pack low enough to proceed. Pink ribbons lead the way, suggesting somebody might come through and make this trail more passable, but alas, it is not today. As we are a hundred feet from the water, a monstrous fallen tree block our path. I tell Red we can drop our packs here and walk to the water.

Red Butt Falls is a unique set among many places I’ve been. My best guess of the name is that it is an easy place to wipe out and bust your butt on the rock during the descent. You cross the creek at the top of the falls and make your way down the left side which is considerably drier but still a little wet if it’s been raining recently. The rock face descends at such an angle that the water glides down the face for what is likely a 40-50 foot drop. It then drops into a pool beneath a massive cliff face that sits over a cave. At the cave, the water careens down the canyon at a sharp 90 degrees to the left, rushes down the hill around massive boulders, then out of sight to the right. The map shows the elusive Lichen Falls around the corner if you’re willing to wade through the water, but I’m usually pressed for time by the time I get this far.

Nevertheless when I come here, I feel on the edge of the known world, completely secluded from all human contact, down, down, down in the valley.

We cross the creek and head down the “drier” side of the rock face, picking our steps carefully. Red explores downstream past the bend while I sit by the pool, watching her. In my moments of solitude, I am the one choosing the extent of my own danger. But I watch her skip around the rocks before I take my own swim, make sure I don’t need to pull her out of the creek. I am not secluded from human contact. I have one very important human to observe and protect.

As Red works her way back up the creek, I try to work up the courage to jump in. I finally cross the pool—swimming against a stiff current—and sit under the cave. I explore the side for spur trails and the depths of the darkness.

But my exploration is short lived. I start to get those goosebumps. I look up above the trees and into the sliver of sky out of this canyon. I know the weather said no rain, but the grey sky above has that sickly look. I have the intuitive worry again, despite what the weather said, so I get Alyssa’s attention and point back toward the trail head, showing her we need to get back. As I cross the water back over, the ominous thunder rolls in. We need to make it to the top quickly, as trying to do so in the rain could seriously complicate things.

As we get to the top, the rain begins to drop. We cross the creek and I head up the trail to change. I tell Alyssa to grab a snack and get ready to leave while I change. I’m worried her lack of breakfast will make her crap out on the walk back. Of course, I’ve left my pack cover at home, and as I’m in the process of putting on dry shorts, the rain falls faster and faster. I rush to put Red’s pack back together and cover it, then run back down the trail to get her to hurry—to get her poncho on, to get ready to hike so that we don’t get stuck here in the rain. She’s only halfway through her snack—a pack of tuna (she’s averse to bars and trail mix and even peanut butter packets, it seems) with no real time to finish it, so I shove it in my raincoat pocket.

By the time we’re donned the rain gear and saddled up to go, it’s full on dumping with rattling thunder. Even though this was half of my trip on the MST this summer, t’s the first time Red’s ever had to hike in serious rain with me. There’s no time to sugar coat this. She needs the truth without illusion. I look her right in the face.

“Hiking in the rain is no different than any other hiking. You just keep going. You’re going to get wet. You have to be careful of the mud.”

One foot in front of the other. You’re going to get wet anyway. Just keep plodding.

Last night at the campfire, our discussion of Greek mythology had led into me telling her about Albert Camus’ interpretation of Sisyphus, to which she had innocently asked, “but why did he keep pushing the rock up the hill? That’s stupid.” I’m thinking of Sisyphus. For Red, this might be the highs and lows of camping, all within a 24-hour period. For me, I’ve done enough hiking in the rain to think of it as the most Sisyphean task. No illusions. Just keep going. You don’t get to stop. That won’t make it any better. Getting mad that it’s raining doesn’t’ help. Looking up at the sky and hoping that it’s going to stop soon doesn’t help. Hoping that someone will swoop in and make this all stop won’t help. You just give into the task, lose yourself in it, and plod on. Just keep pushing that rock.

The trail that was treacherous and slow 45 minutes before is much more the challenge in the sheets of rain. But we plod on. I warn her about the slippery mud, but otherwise we hike in silence, pushing through the rain. Soon, we make it to the trail junction just as the rain starts to lighten, doing the worst part of the trail under the worst conditions. It was never as far as we feared. I reach in my pocket and hand her tuna back to finish her snack. The rain is a slow drizzle, so I take off my coat and hang it on my pack.

It’ll be about 2.5 miles back to the car, and I know she might struggle with some uphills. My Sisyphean solution is just to keep walking. Establish a pace that you can sustain. Put one foot in front of the other. Soon, the walking becomes automatic, even meditative, even ecstatic—an out-of-body experience.

But before I get all spiritual on hiking, I have to remember this is my intuition—learned through thousands of miles that establish a rhythmic gait. I have to remember that she is 12. I have to remember that as hiking goes, coming back to the parking lot—an elevation gain of 969 feet—with her full pack after the rainstorm is the hardest thing I’ve ever asked her to do. For me, the “face the reality of your current fate” perspective of Camus might be enough, even invigorating as I cross the finish line. But that won’t work if I don’t get her to come along. I know if I push her too hard or become impatient, she could easily become dispirited. I don’t want her takeaway from the trip to be that I tried to make this about my pace, making it miserable for her. Sorry Camus, it’s time for some diversions as we finish the hike.

We start by looking back at the fungus, easy as we go downhill back to the creek crossing. Most of them have upturned into tiny bowls to drink of the rain. But after the creek, we have more uphills, and she often lets out a lament of woe when she sees the trail snaking upwards, taking a bend over her trekking pole to catch her breath. We switch tactics to keep our spirits high on the return by singing songs, making up stupid lyrics to popular tunes. As long as we are trying to remember how tunes go, or thinking about what we can sing about, or making up stupid lyrics, the legs keep churning.

She asks how much longer, and I tell her we should be back at the car within the next 1.25 miles. Finally, to get us near the finish line, we begin the “food fantasy” stage of the hike. All hikers know this, and I explain it to her: it’s where you start day dreaming about the food you’ll get once you get off the trail. I know what she wants: cheeseburger, ketchup only, and French Fries. I dream of a warm drink, like a hot chocolate. She wants one of those, too. I tell her we can get that. “Are you sure?” she asks, “because sometimes people say we can get food, but then we don’t.”

“I promise.”

I can tell she’s near the end of her rope. She’s stopping more frequently, and we have a moderate climb to the car. She didn’t even notice that we turned left of the Panthertown trail, which signifies about .8 miles back to the car. I tell her this and it gives a little hope. Two ladies show us a shortcut I’ve never seen, so that cuts off a bit more distance. But it’s steeper. At the top, she bends over her pole again. I think about taking her pack off of her, but I also don’t want to deprive her of the satisfaction of finishing this herself. Camus may have snorted at the songs and the food fantasies, but one thing that he would have respected about backpacking is that your pack is your pack, and your burden is your own. When you finish, you are stronger for having carried it, but it is your rock to roll up the hill and no one else’s. So, while I want to help her in her distress, I choose to only do it through encouragement.

We turn right at the red gate and over the bridge. We’re in the homestretch, five minutes or so of climbing over roots. We can see the space in the trees near the power lines where the parking lot finish line sits. I keep telling her to look to the light, that I can see the cars through the trees. Then I hear her yelp in pain. She asks me to take off her shoes. I can see the spot, but there’s no culprit.

“What was it?”

“I don’t know. I didn’t see it.”

There’s nothing in her boot, and as long as it’s not a snake, I think she’ll be okay. I ask her if she can make it to the car. She can. She gets in and just as we get everything into the car, it begins to rain again. We’ve pushed our rock to the top of the hill, but the conditions are not celebratory. Besides, now we have to roll a rock of a different nature down the road.

We’re on the road about 2:30. We take a right on 64 and head West. We stop at a Dollar General so I can get some ice and pain relief for her now swelling ankle. Then we look for a quick bite I promised her on the trail

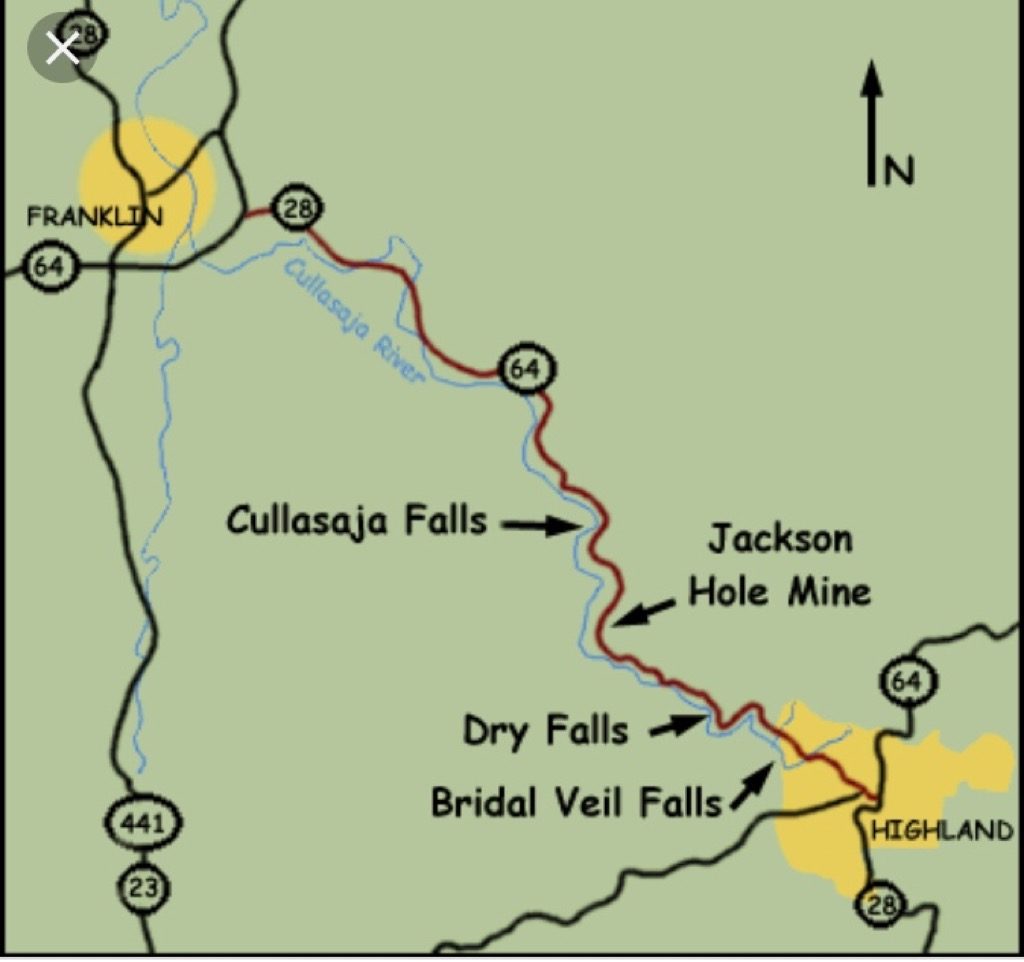

Except there are no burgers. 64 west from P-Town is a meander through gated resort communities. There are restaurants, but I don’t see any that are a quick grab-and-go that we need. There’s an Ingles near Highlands, but I figure if we can make it to Franklin, there are restaurants there. Our spirits are still pretty good as we talk about the hike, continue some of our conversations from the previous night, and yuk it up listening to some of the local radio stations. For all the miles hiked, it is often these small moments, moments of shared humor and suffering that coalesce human relations, and these jokes we will likely remember as much as anything about this trip.

Then we get stuck in a traffic jam on 64. If you’ve never traveled this road, it’s a long, windy two-lane with limited visibility. I look on the map. There’s no place to turnaround and connect later. This is the road we have to take. There’s no short cut or turn around for us. We have to plod on by sitting in this place.

It’s an hour before we see emergency crews come past us on the left. We never know what the cause was. Back in motion. Back through the storm. Back looking for food.

But 64 is pretty barren in this way. I begin to get the impression that had I planned better—and had we taken the early hike-out option that this part of the trip could be better. The Cullasaja River Gorge has lots of waterfalls to see. A little drier and earlier and it might be fun to step out of the car and see the various sights. But as it is, we’re going to make Decatur near night fall, and there’s little time for side trips. I feel sure that we can get food in Franklin, but 64 skirts the lower part of the town and we miss everything. There’s a Wendy’s as we roll out of town, but at this point Red is not impressed and wants to hold off for something better.

But after Franklin, we go back into long, beautiful roads winding through tall mountains and cow pastures. Red is sleeping by now, so I start counting cows and building a lead. Near Hayesville, Chatuge Lake stretches to the South, but again the dictates of time keep the boats on the racks. I stop to get gas and tea to kick me into the home stretch. In Murphy, about four hours since leaving the parking lot, Wendy’s is still the best option off 64, so we concede, hit the drive through, and keep going.

Despite the swelling in her ankle, I’m glad Red is in good spirits. The ending of the hike, the long wait for food, could easily have soured her outlook. It makes me wonder if I made the bad decision at the outset of the day, and how the day would’ve been any different if we had just hiked out. Of course, my Honda is not a time machine, so this is moot. But as I see all the wild water near the border and as we cross into Tennessee, I think how I could’ve planned this differently. We start to dive into the Occoe Wild river area, where the ’96 Olympic kayaking was held, where for a few summers I spent many a weekend, and I nostalgically tell Red of all the river trips we used to pull back in the day. She’s on board, and maybe when she’s a little bigger, a little more adept at handling herself in a boat, we can make a trip back here for that. I tell her it eventually opens into a huge lake. It opens to the south of us, and Red sees the islands in the middle of the lake.

“Those look fun” she says. The sky is getting golden, and had we a few more hours, had I known we were going to be here, it would’ve been nothing to pull the boats off the truck and paddle for a couple of hours. We probably could’ve planned an afternoon around that. But we didn’t. That is not the path we have chosen. So for now, Occoe (only an hour from our destination) gets filed under the “Future stops on Future Road Trips” file. The rough hike and sting have not soured her, and that is a win. That is hope for the next trip. We leave the lake and head into Cleveland, where we motor to the interstate.

With food in our bellies, we are a little better of spirit. I tell Red that this is the part of the world where the Cow Game* was born, and that she is down 18 cows since she was asleep through Hayesville and Murphy. We take 75 north from Cleveland for about 45 minutes, then we are on some serious back roads in rural Tennessee and the game is on again. She closes the gap before we pass a church on the left whose graveyard is on the right, resetting her to zero. Another church on the right warns us that “Hell is totally uncool.” We chuckle, and she implores we come back and take a picture when we leave, but I tell her I don’t know if we take this road again. File it away under inside jokes. A few more pastures, some no-point, no-count jackasses. Then, on the main road again.

We pull into the farm around 8:30, and even though we pass a pasture on the right, I finish the day with a dominating 76-10 win. Calico, the neighborhood dog comes out to greet us, and Marcie helps us get our wet things out of the car. We sit up a bit over snacks and chat, but we are wiped out and soon to bed. At least for now, after five hours of hiking and six hours of driving, our burden can come to rest for the evening, and we can get the rest at the top of the hill.

*The Cow Game is a road-trip game in which you count points for your side of the car. The winner gets bragging rights and eternal glory.

Cows =1 pt.

Horses=2 pts.

Cemeteries=reset back to zero.

Recent Comments